Process evaluation is increasingly recognized as an important component of effective implementation research and yet, there has been surprisingly little work to understand what constitutes best practice. Researchers use different methodologies describing causal pathways and understanding barriers and facilitators to implementation of interventions in diverse contexts and settings. We report on challenges and lessons learned from undertaking process evaluation of seven hypertension intervention trials funded through the Global Alliance of Chronic Diseases (GACD).

Preliminary data collected from the GACD hypertension teams in 2015 were used to inform a template for data collection. Case study themes included: (1) description of the intervention, (2) objectives of the process evaluation, (3) methods including theoretical basis, (4) main findings of the study and the process evaluation, (5) implications for the project, policy and research practice and (6) lessons for future process evaluations. The information was summarized and reported descriptively and narratively and key lessons were identified.

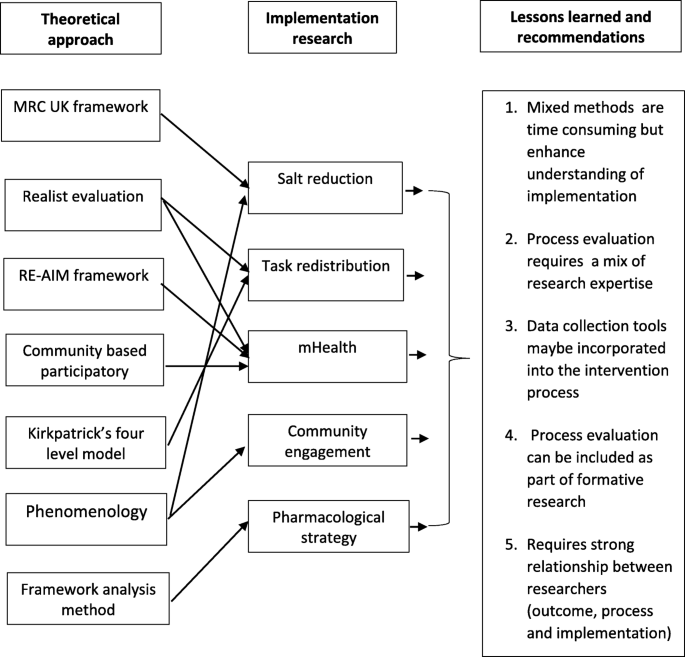

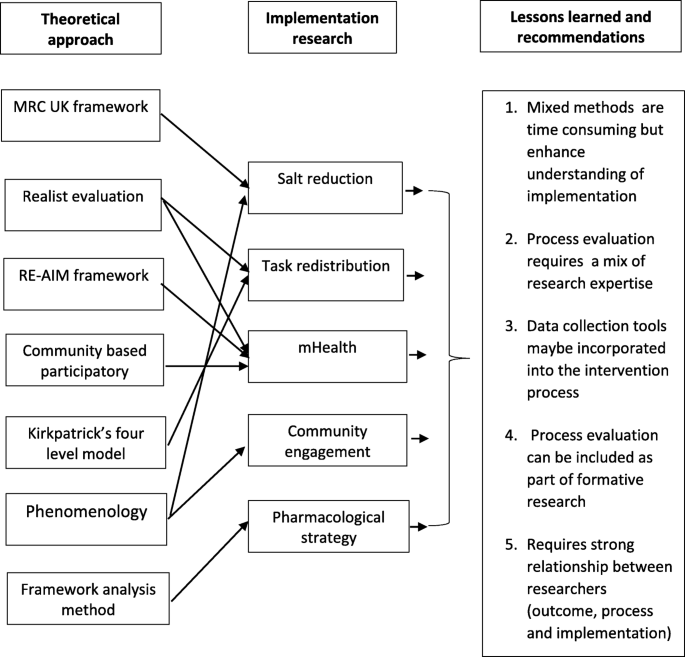

The case studies were from low- and middle-income countries and Indigenous communities in Canada. They were implementation research projects with intervention arm. Six theoretical approaches were used but most comprised of mixed-methods approaches. Each of the process evaluations generated findings on whether interventions were implemented with fidelity, the extent of capacity building, contextual factors and the extent to which relationships between researchers and community impacted on intervention implementation. The most important learning was that although process evaluation is time consuming, it enhances understanding of factors affecting implementation of complex interventions. The research highlighted the need to initiate process evaluations early on in the project, to help guide design of the intervention; and the importance of effective communication between researchers responsible for trial implementation, process evaluation and outcome evaluation.

This research demonstrates the important role of process evaluation in understanding implementation process of complex interventions. This can help to highlight a broad range of system requirements such as new policies and capacity building to support implementation. Process evaluation is crucial in understanding contextual factors that may impact intervention implementation which is important in considering whether or not the intervention can be translated to other contexts.

A substantial challenge faced by implementation researchers is to understand if, why and how an intervention has worked in a real world context, and to explain how research that has demonstrated effectiveness in one context may or may not be effective in another context or setting [1]. Process evaluation provides a process by which researchers can explain the outcomes resulting from complex interventions that often have nonlinear implementation processes. Most trials are designed to evaluate whether an intervention is effective in relation to one, or more, easily measureable outcome indicator (e.g. blood pressure). Process evaluations provide additional information on the implementation process, how different structures and resources were used, the role, participation and reasoning of different actors [2, 3], contextual factors, and how all these might have impacted the outcomes [4].

Several authors have argued that in complex interventions, process measures used to examine the success of the implementation strategy, must be separated from outcomes that assess the success of the intervention itself [5]. The recent Standards of Reporting Implementation Studies (StarRI) statement consolidates and supports this concept [6, 7]. Given the significance of the causal pathway of a research intervention, which is crucial to future policy and program decisions, it is helpful to understand how different research programs, in different settings, employ process evaluation and the lessons that emerge from these approaches.

Since 2009, the Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases (GACD) has facilitated the funding and global collaboration of 49 innovative research projects for the prevention and management of chronic non-communicable diseases [8] with funding from GACD member agencies. Footnote 1 Process evaluation has increased in importance and is now an explicit criterion for project funding through this program. The objective of this paper is therefore to describe the different process evaluation approaches used in the first round of GACD projects related to hypertension, and to document the findings and lessons learned in various global settings.

Preliminary data on how the projects planned their process evaluations, were collected from the 15 hypertension research teams in the network in 2015 and was used to develop a data collection tool. This tool was then used to collate case study information from seven projects based on the following themes: (1) description of the intervention, (2) objectives of the process evaluation, (3) approach (including theoretical basis, main sources of data and analysis methods), (4) main findings of the study and the process evaluation, (5) implications for the project, policy and research practice and (6) lessons for future process evaluations. The case study approach recognizes that projects were at different stages of intervention/ evaluation. Each process evaluation was nested within an intervention study that was either completed or nearly completed.

Information relevant to each of the agreed themes was documented by FL and JW using a data extraction sheet (see Table 1). The information was summarized and reported descriptively and narratively in relation to the themes above. Overarching issues were identified by the working group that had been established to oversee the project. The working group comprised researchers who had all been involved in the different process evaluations and helped to draw out the main implications of the process evaluation with respect to project and policy, as well as lessons to inform future process evaluations.

Incorporating process evaluation data collection tools into the intervention process from the onset was identified as crucial for process evaluation. Process evaluations cannot be conducted retrospectively as investigators cannot go back and collect the required data. For instance, for the clinic based LHW intervention in South Africa, it was ideal to observe and understand how nurses interacted with the intervention as it was being implemented. Thus, process evaluations should be fully embedded into the intervention protocol or a separate process evaluation protocol should be developed alongside the intervention protocol. In Sri Lanka, collecting process evaluation data before the study outcome data were available helped in exploring implementation processes without unintentionally influencing investigator or patient behavior in the study.

Some investigators who commenced their process evaluation after the intervention had begun, e.g. the CHW project in Kenya, felt that it may have been helpful to have started this earlier in the study life-cycle. Other investigators who incorporated process evaluation in formative research and situation analyses reported that this approach helped identify which specific process measures should be collected during the intervention. One study team deliberately did not collect process evaluation data until after the study was complete so as to not affect investigator or patient behavior in the study itself. Therefore multiple considerations should be taken into account when designing process evaluations.

Experiences from six of the projects support the MRC recommendation for strong relationship and consultations between researchers responsible for the design and implementation of the trial, outcome evaluation and process evaluation [2]. However, whilst the teams reported positively on coming together to exchange experiences at different stages of the project, it was felt that additional interim assessments of process throughout the project would have further strengthened implementation of the interventions. In some teams, discussion of the preliminary results of the process evaluation by the broader project group, including local country teams, was an essential part of the data synthesis and greatly enhanced the validity of the results by clarifying areas in which the researchers might not have understood the data correctly.

The DREAM GOBAL process evaluation demonstrated the need for formative research that informed the mHealth projects for rural communities in Tanzania and Indigenous people in Canada as well as the value of using a participatory research tool [28]. This tool helped to identify: a) key domains required for ongoing dialogue between the community and the research team and b) existing strengths and areas requiring further development for effective implementation. Applying this approach, it was found that key factors of this project, such as technology and task shifting required study at the patient, provider, community, organization, and health systems/setting level for effective implementation [7].

The analysis of process evaluations across various NCD-related research projects has deepened the knowledge of the different theoretical approaches to process evaluation, the applications and the effects of including process evaluations in implementation research, especially in LMICs. Our findings provide evidence that, whilst time-consuming, process evaluations in low resource settings are feasible and crucial for understanding the extent to which interventions are being implemented as planned, the contextual factors influencing implementation and the critical resources needed to create change. It is, therefore, essential to allocate sufficient time and resources to process evaluations, throughout the lifetime of these implementation research projects.

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ministry of Science, Technology and Productive Innovation (Argentina), National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia), São Paulo Research Foundation (Brazil), Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Research & Innovation DG (European Commission), Indian Council of Medical Research, Agency for Medical Research and Development (Japan), The National Institute of Medical Science and Nutrition Salvador Zubiran (Mexico), Health Research Council (New Zealand), South African Medical Research Council, Health Systems Research Institute (Thailand), UK Medical Research Council and US National Institutes of Health

Accredited social health activist

Community health worker

Focus group discussion

Global alliance for chronic diseases

Lay health worker

Low and middle-income countries

Medical research council

Reach, efficacy, adoption, implementation, maintenance

Short message service

Standards for reporting implementation studies

We appreciate the contributions and participation of the rest of the members of the GACD Process Evaluation Working Group. These include: Alfonso Fernandez Pozas, Anushka Patel, Arti Pillay, Briana Cotrez, Carlos Aguilar Salinas, Caryl Nowson, Claire Johnson, Clicerio Gonzalez Villalpando, Cristina Garcia-Ulloa, Debra Litzelman, Devarsetty Praveen, Diane Hua, Dimitrios Kakoulis, Ed Fottrell, Elsa Cornejo Vucovich, Francisco Gonzalez Salazar, Hadi Musa, Harriet Chemusto, Hassan Haghparast-Bidgoli, Jean Claude Mutabazi, Jimaima Schultz, Joanne Odenkirchen, Jose Zavala-Loayza, Joyce Gyamfi, Kirsty Bobrow, Leticia Neira, Louise Maple-Brown, Maria Lazo, Meena Daivadanam, Nilmini Wijemanne, Paloma Almeda-Valdes, Paul Camacho-Lopez, Peter Delobelle, Puhong Zhang, Raelle Saulson, Rama Guggilla, Renae Kirkham, Ricardo Angeles, Sailesh Mohan, Sheldon Tobe, Sujeet Jha, Sun Lei, Vilma Irazola, Yuan Ma, Yulia Shenderovich.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the following GACD program funding agencies; National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (Grant No. 1040178); Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom (Grant No. MR/JO16020/1); Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant No. 120389); Grand Challenges Canada (Grant Nos. 0069–04, and 0070–04); International Development Research Centre; Canadian Stroke Network; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. U01HL114200); National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. 5U01HL114180); National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (Grant No. 1040030); National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (Grant No. 1040152).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Funders. The authors declare that the funders did not have a role in the design of the studies and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.